feature: Modern Day Matchmaking

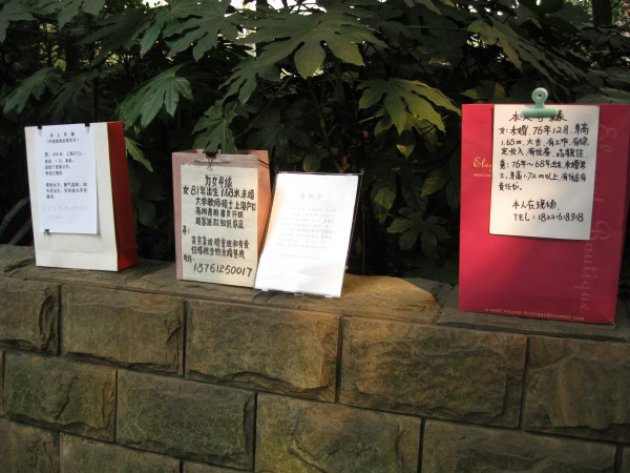

On the northern edge of People’s Park not far from the always bustling Nanjing Lu, a uniquely Chinese social phenomenon takes place every Saturday and Sunday afternoon. A large group made up of middle-aged parents and elderly grandparents assemble to trade basic information on their offspring in hopes of finding a potential spouse for their son or daughter. Thousands of slapdash personal advertisements, revealing things like year of birth, height, education level, job, salary, property owned, hukou and occasionally a picture, hang from bushes, a tent covered clothesline or lay strewn on the ground battened down by a rock or clump of mud. Welcome to the Shanghai Marriage Market.

Although the idea of parental involvement in the search for a husband or wife may seem foreign to many modern Western cultures, this matchmaking tradition has been a central tenet of Chinese society for thousands of years. Mr Zeng, an affable father in his 50s, explains, “In China, it is the parents’ responsibility to find a suitable suitor for their children.” Whether their children agree with their approach is a different matter, with some unaware their parents are touting them behind their backs.

In Zeng’s case, his daughter is well aware, having already accommodated her father by going on a series of dates with his prospective husband choices. “I have been coming here for two years now, twice a week,” he admits. “My daughter has gone on over 20 dates – mostly Chinese men, but also Italian, French, even an American – but so far she hasn’t found a match.”

In Zeng’s case, his daughter is well aware, having already accommodated her father by going on a series of dates with his prospective husband choices. “I have been coming here for two years now, twice a week,” he admits. “My daughter has gone on over 20 dates – mostly Chinese men, but also Italian, French, even an American – but so far she hasn’t found a match.”

For her it is a simple case of not enough time, her busy work schedule precludes her from having an active dating life on her own. She seems like a good catch for any man lucky enough to pique her interest, having studied abroad in Australia and holding a good job with a foreign education company. The picture Zeng triumphantly holds up shows a very pretty young woman in her mid-20s. “She has no time to find a husband, so I am looking for someone who will make her happy,” he says.

In China, the pressure to get married increases as a child ages through their 20s. It is commonly accepted that marriage, and most importantly the beginning of a family, should happen before the age of 30. For women especially, this familial and societal pressure can be heavy, lest she be negatively thought of as a shengnü, or leftover woman. It’s a term of shame without a male equivalent, and one that can add to a parent’s desperation.

As if to prove the point, matchmakers who set up shop amidst the distressed parents are willing to supply potential brides with copies of a hand-written list of 300 potentially suitable male candidates for RMB 30. Grooms-to-be can get an equivalent list of females for just RMB 5. Matchmaker Qian, whose painstakingly scrawled pages could easily fill a three-ring binder, has been earning his spending money finding suitable companions since he retired five years ago. According to Qian, lists of grooms cost more because of simple supply and demand; more women are looking for husbands, despite the fact that Shanghai’s sex ratio skews male.

Not all matchmakers are looking to make a buck from the desperate in-laws-to-be. Matchmaker Ma took up the trade after retiring from a cushy civil service engineering job. Every weekend, she sits beside her cohort Ms Cheng as the two play Cupid for free. Both practicing Buddhists, they declare they are just volunteering to help facilitate a couple’s yuanfen, loosely translated as “fate that brings people together”, an oft-repeated phrase at the market. All Ma and Cheng expect in return for their services is a seat at the wedding banquet, but they won’t work for just anyone.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

Recent comments

5 days 17 hours ago

1 week 3 days ago

2 weeks 59 min ago

2 weeks 2 hours ago

2 weeks 5 hours ago

2 weeks 22 hours ago

2 weeks 22 hours ago

3 weeks 1 day ago

3 weeks 1 day ago

4 weeks 3 days ago